Empowerment Through Chaos - How Mumbo Jumbo Represents Essential Black Arts Movement Literature

Mumbo Jumbo certainly has its fair share of quirks—random images and drawings, weird syntax, crazy layout—all these things that you would never encounter in so-called regular literature have such a commanding, in-your-face presence within Reed’s novel. While I was reading the book, though, I found myself thinking: what was the purpose of all these nonconformities? For a while, it was almost off putting to deal with all of Reed’s nonsense; it felt as though he was just including weird elements for no reason other than simply to be weird. Once looking at it from a different perspective, however, the craziness carries another meaning, one that gives an exemplary representation of Black empowerment.

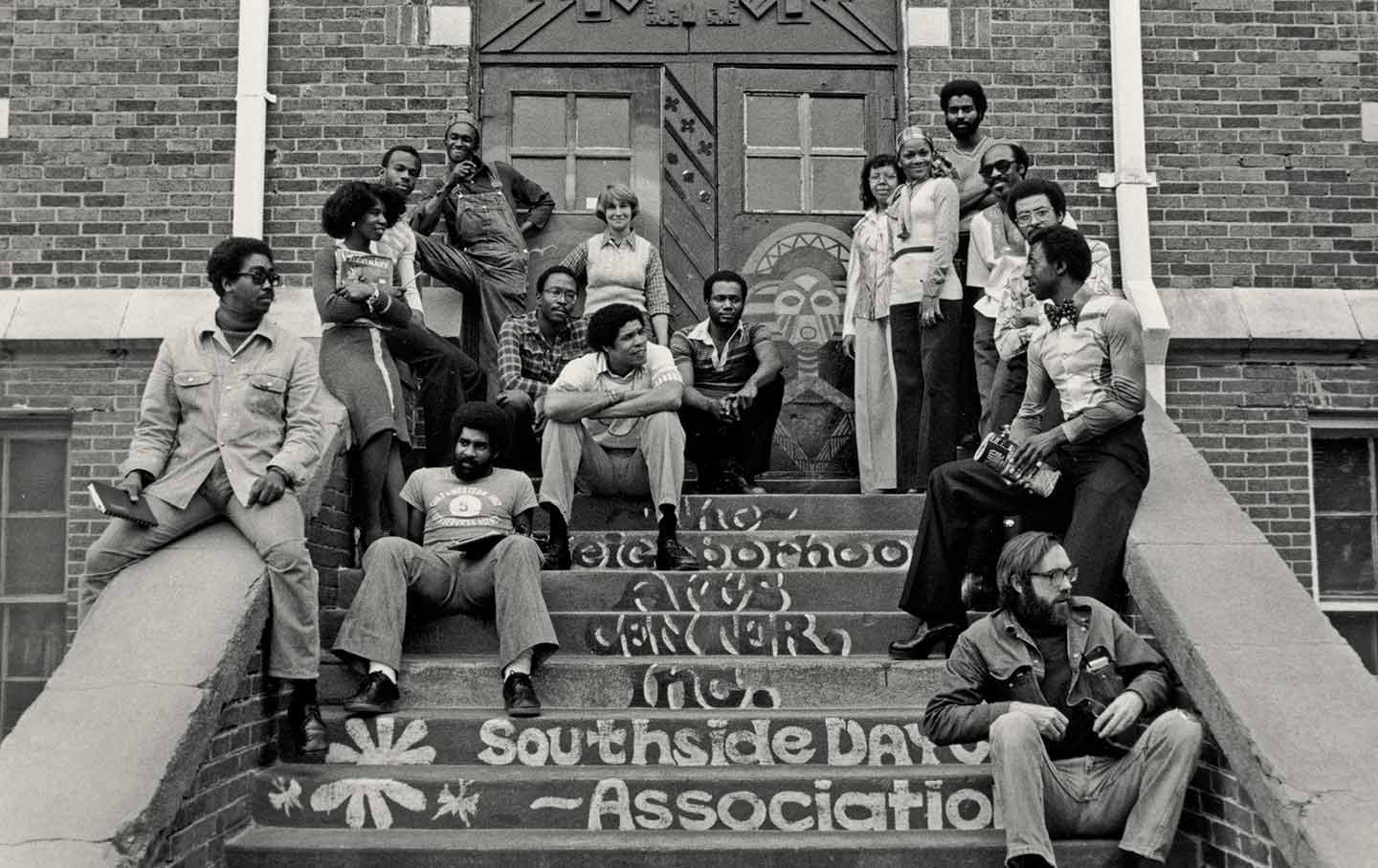

Mumbo Jumbo was originally published in 1972, at the peak of the Black Arts Movement, which you’ll recognize if you’ve ever taken African American Literature with Dr. E. To summarize, the Black Arts Movement, or BAM, was a time not unlike The Harlem Renaissance in its concept. It was a time which saw a resurgence of African American authors, musicians, artists, and activists alike, though this time, they had a different goal from those of the 1920s: rather than taking mainstream media and adding an African spin, the artists of the BAM sought to completely reject European art forms and the mainstream itself, instead opting for a completely new and unique style. These BAM works would often find crazy and creative ways to distance themselves from the norm, and would often target a primarily African American audience instead of trying to appeal to the masses like in The Harlem Renaissance; it was Black art for Black people.

The characteristics of BAM literature are very clearly identifiable in Mumbo Jumbo: the crazy syntax, grammar, and layout aren’t just there for the sake of being different, they seek to put pride in Black arts by creating a new and exclusive means of expression for African Americans. Even within the story itself, there is an evident rejection of European ideals; in Papa LaBas’ long explanation towards the end, we see the traditional Christian story get flipped on its head, even being replaced with a completely different history which, critically, has African religion and figures at its center. By putting African people in the spotlight of history from which they had been denied for so long, Reed and other BAM artists encouraged Black people to have more pride in themselves and their heritage.

Even more telling are the somewhat ironic depictions of White people in Mumbo Jumbo. We spoke in class about some White people potentially being offended by Reed’s portrayal of them, which I think speaks volumes about the intended audience of the book. One such instance is when Reed remarks on Hinkle Von Vampton’s lips, saying that he daubed “his 2 faint pink lines where lips should be.” (80). It’s almost as if Reed isn't intending for a White person with said “faint pink lines” as lips to even be reading the book at all; that this piece of literature wasn’t meant for mass consumption, but rather to empower African American artists to create and experiment with their own, exclusively Black forms of expression.

All in all, Mumbo Jumbo is a very complex book that does a lot of things at once. But there is method to the madness, and every seemingly out-of-place element was placed with intention. Honestly, once you get past the initial absurdity of the novel and around to understanding the plot, it's sort of fun to decipher the oddities and see what subliminal messages they may be hiding.

(nice AFAM Lit Shoutout btw) Yeah, as I've been able to sit back and digest this book more and more over break, the more I've also been able to notice the connections that this book has with B.A.M. In the grand scheme of things, I guess it makes sense why this book is the way it is. Absurd, throwing in elements that don't make a lick of sense, short but also long at the same time, including 70s references and slang at random points, even in the flashback to Jes Grew's history. One of the interesting things that I had noticed in class (before break started) was that Jes Grew seems to have a resurgence throughout major black movements in history: 1920 was the Harlem Renaissance, and Jes Grew popped up there. In the end of the story, it's implied that it comes back again with 1970, which is right when the Black Arts Movement starts and when Reed writes the book

ReplyDeleteI think it is really interesting how complex the storyline seems at surface level, just because he is introducing so many concepts most readers don't understand, but as you peel back the layers, the book truly does start to because simplistic in its plot and has a lot of cohesion with the way the story fits together and culminates over time. In a sense, you really won't appreciate the book until you're done reading it because every confusing detail placed at the beginning will eventually amount to something in the end. In this way, Reed crafts a novel that demands the readers attention to detail, but at the same time, one that rewards the attention of the reader to produce a ending that truly does make (almost) everything make sense. Sure, there are small sytlistic choices that are harder to decipher, but for the purposes of a first time Reed, it ended up having a satisfying conclusion. For example, I remember the whole concept of Jes Grew "wanting to find its text" was extremely confusing at first but one thing you can count on Reed doing is explaining his major narrative choices. Sure enough, there ended up being an entire set of chapters dedicated to explaining the origin of the book which cleared up its fictional siginifance for me in the context of the novel and gave it a sense of resolution, regardless of the initial frustration and confusion in trying to figure out why the anti-plague needed a text.

ReplyDeleteI have not learned about BAM before, so this is really good context for me to process the (seemingly random) abnormalities of Mumbo Jumbo. The idea that the BAM artists sought to create their own form of art specifically targeting an African American audience is very interesting, especially when considering it in the context of Mumbo Jumbo's plot. Toward the end of the novel, LaBas makes a remark that the future generation (of black people) will create its own form of Text. This notion of creating a new cultural basis from scratch reflects BAM's vision of reinventing art for African American people and hints at the idea that Mumbo Jumbo itself might be the new Text, embodying the explicit contradiction of mainstream white cultural norms in ways that you have outlined in this blog.

ReplyDeleteAs someone who's never taken a dedicated African American Lit class, you did a great job in explaining the connection to BAM. I too felt like there were a lot of random moments scattered around the story that seemingly had no purpose, but now I see that they were there specifically to defy readers' expectations and change our views on how literature can be. Reed's use of unconventional formatting and mixed media elements help him achieve this goal.

ReplyDeleteYou're right that there are a number of parallels between the BAM and the Harlem Renaissance--which Reed alludes to with his mention of "history as a pendulum" at the end of the novel, where he outright declares that the 1970s will represent the "return" of the 1920s. But at the same time--and we see this pretty clearly in Reed's novel--the BAM writers (and Reed) could be quite critical of the Harlem Renaissance, not so much the work and intentions of the artists and writers themselves, but the ways the movement was limited and co-opted by figures like Carl Van Vechten (who Reed parodies with fierce irony as Hinckle Von Vampton). In _Mumbo Jumbo_ we see this great *potential* for the HR to really break through and make a lasting incursion into Atonist dominance, but in Reed's version the movement fails to fully achieve these aims. (In part because the Wallflower Order initiates the Great Depression and people can no longer afford radios, but also because--as we see at the "gathering of Black artists" at which Safecracker performs in blackface--the movement has already been undermined by Atonists. Reed seems to see much more hope and potential in the Black Arts Movement and his West Coast Afrocentric/Pre-Columbian literary movement.

ReplyDeleteI definitely agree that Mumbo Jumbo is a work of the black arts movement, and I remember thinking that it seemed to be using a lot of the same techniques while reading it. Looking at it now, it's definitely clear that the black arts movement is probably what Reed's talking about at the end of the book as the pendulum swinging back. I can also see how this book is a rejection of traditional western styles of writing, like how he puts the first chapter before the title page, and breaking up the text with seemingly random images. I also wonder what this book would look like if he went even farther with that, or whether it would still even be a novel. Also since we're on the topic of Dr E classes, I think there are also some elements of Afrofuturism in this book as well.

ReplyDeleteI think your point on not being for a large appeal is right—many of the seemingly 'prejudiced' representations that are found in Mumbo Jumbo could be misinterpreted if marketed as a popular fiction novel, notwithstanding its complicated prose. I also agree with your position that Reed's reframing of the historical origins of Jes Grew serves as to further inspire African American artists—by reframing and/or retelling the such an important narrative, its possible to convey a sort of inspiration.

ReplyDelete